Disparity in children’s environments

Child poverty in Japan: hidden from view

Senior Researcher

Economic Research Department

Daiwa Institute of Research Ltd.

Japan is a rich nation—is child poverty really such a serious problem? The difference today is that poverty is hidden from view; for this reason, it is vital we use data to visualize the reality of child poverty.

1. Child poverty close to home

When measuring poverty, using absolute income levels is appropriate if it is a question of the minimum income required to survive—as in developing countries, for example, or post-war Japan.

On the other hand, in developed countries and in general use, poverty is defined as having an income level below which there is a risk that a person lacks the resources necessary to lead a dignified life—this can take various forms, but includes becoming more socially isolated, or suffering deteriorating health.

This is known as the “relative poverty rate,” and is defined as the percentage of people who do not earn half or more of the median per person household income in that country. It is known as the “relative” poverty rate, since it defines poverty as a relative income.

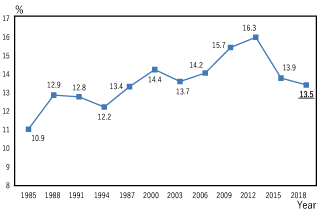

Child poverty rates

- Note: “Child poverty rate” is defined as the percentage of children aged 17 or below, whose equivalent disposable income is below the poverty line

- Source:Compiled by the Daiwa Institute of Research, based on the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s “Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions”

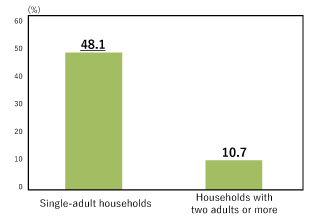

Poverty rates among working households with children, by household type (2018)

- Note:“Poverty rates by household type” is defined as the percentage of the total population living in working households—whose head is aged between 18 and 64—whose equivalent disposable income falls below the poverty line.

- Source:Compiled by the Daiwa Institute of Research, based on the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s “Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions”

Released in December 2020, the latest government data for 2018 shows that child poverty rates have improved a little to 13.5%.

Following its 2012 peak, one of the reasons behind this improvement is the influence of Abenomics, which has raised incomes among low-income households.

However, COVID-19 has led to decreased incomes among low-income households in particular; for this reason, there is a possibility that child poverty rates could be on the rise again.

The Luxembourg Income Study Database enables us to compare poverty rates in Japan with those in other countries. Data shows that Japan’s poverty rates are lower than the U.S. and Spain and other countries in southern Europe, similar to Australia and France, but higher than Finland and other countries in northern Europe.

Japan’s child poverty rates are distinctive for the fact that poverty is most prevalent among single-adult households. Poverty rates are particularly severe among mother-child single-parent households.

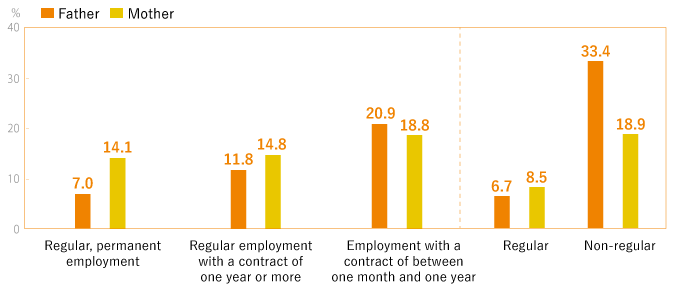

One cause is that many women hold non-regular forms of employment, and are therefore more likely to work low-paid jobs.

In father-child single-parent households, too, child poverty rates are particularly high when fathers hold non-regular forms of employment.

The traditional Japanese employment and social system—in which the husband is a regular, permanent employee and in which the wife is a full-time housewife—is no longer appropriate for the present age; and this unsuitability is manifesting itself in the form of child poverty.

Child poverty rates, by parent employment type (2012)

- Note: “Regular” refers to regular workers and employees with either permanent employment contracts or employment contracts of one year or more; “Non-regular” refers to part-time workers, temporary workers, contract workers, commissioned workers, and others; with regard to people on one-day contracts or contracts of less than one month, the sample size was too small to include in poverty rates.

- Source:Compiled by the Daiwa Institute of Research, based on “Trends in Relative Poverty Rates: 2006, 2009, and 2012,” by Aya Abe (2014), published on the HinkonStats (“Poverty Statistics”) website

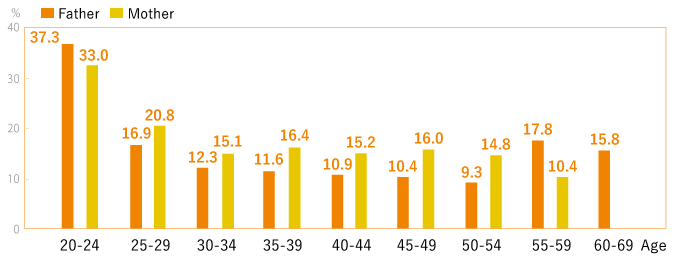

Child poverty rates, by parent age (2012)

- Note:Ages refer to ages of parents in 2012

- Source:Compiled by the Daiwa Institute of Research, based on “Trends in Relative Poverty Rates: 2006, 2009, and 2012,” by Aya Abe (2014), published on the HinkonStats (“Poverty Statistics”) website

However, the reality of child poverty does not always align with a conventional image of what poverty looks like.

The reason for this is twofold: first, poverty is defined in relative terms; second, all children today tend to own similar possessions, whether they live in poverty or not.

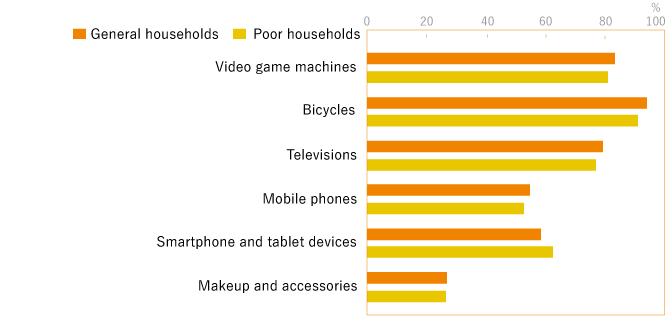

For example, there is little difference in the percentage of general households and the percentage of poor households that have video game machines, bicycles, mobile phones, or smartphones.

This is no doubt due in part to the fact that products in general cost less nowadays, and that most Japanese households earn sufficient incomes to purchase such products.

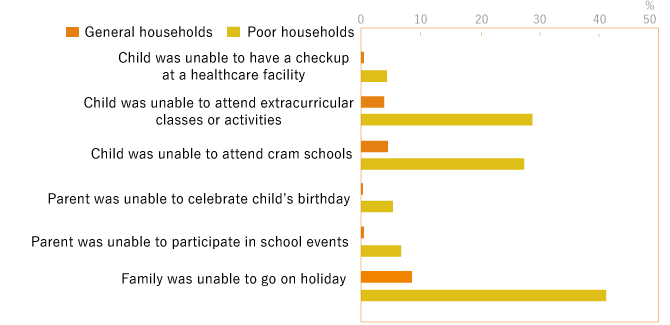

However, children of poor households are disadvantaged in terms of the experiences they enjoy—they may be unable to attend extracurricular activities, for example, or go on family holidays.

Parents of low-income households also tend to work longer hours, and for this reason they cannot spare the time to provide their children with experiences. It may well be they try and make up for this shortfall by at least providing their children with possessions.

The fact that poverty manifests itself in consumption of services is one of the reasons why child poverty remains hidden from view.

Differences in child possessions and experiences, by household type (Osaka Prefecture, 2016)

- Note:The graphs show results from all local governments in Osaka Prefecture; “General households” are defined as households with equivalent disposable incomes at or above the median line; “Poor households” are defined as households with equivalent disposable incomes of less than 50% of the median line

- Source:Compiled by the Daiwa Institute of Research, based on “Factual survey into the lives of children in Osaka Prefecture,” by Osaka Prefecture University (March 2017)

2. Economic and social impacts

Child poverty is a serious issue because, in addition to the impact it has on children throughout their childhoods, it has a tendency to lead to adult poverty and to disparities in adult income.

The most significant way in which poverty creates chains of poverty and income disparity is education.

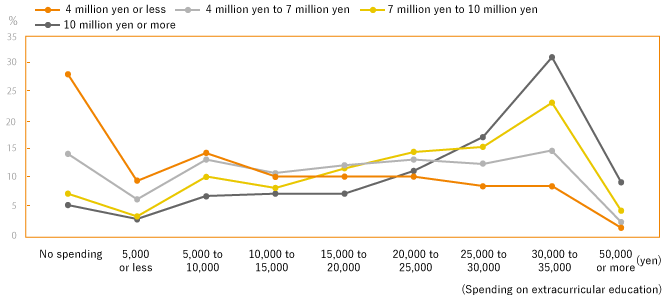

Japan’s compulsory education system entitles all children to receive education, regardless of the income of their parents. However, the reality is that there is a link between parent income and child academic ability.

Since households with higher incomes tend to spend more on cram schools and extracurricular lessons, parent incomes can have a significant impact on the academic and cognitive ability of their children.

Spending on extracurricular education, by household income (for third-grade junior high school students)

- Note:“Household incomes” show pre-tax incomes; “Spending on extracurricular education” is defined as average monthly spending per child on cram schools and other lessons outside of school

- Source:Compiled by the Daiwa Institute of Research, based on “Analysis of impacts on academic ability, based on the FY2013 National Assessments of Academic Ability,” by Ochanomizu University (March 28, 2014)

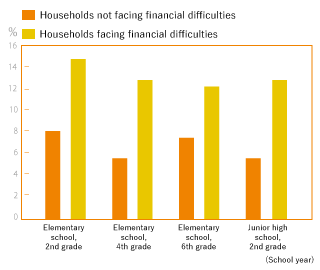

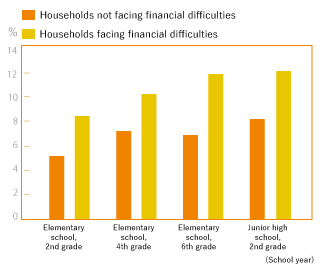

Percentage of children who have poor “Ability to overcome adversity,” by household type (FY2016)

- Note 1:“Households facing financial difficulties” are defined as households that fulfill at least one of the three following criteria: a household income of 3 million yen or less; a household with a lack of daily necessities; a household that has had difficulties meeting payments in the past

- Note 2:Numbers refer to the percentage of children classified among the worst-performing groups when it comes to “Ability to overcome adversity”

- Source:Compiled by the Daiwa Institute of Research, based on “Second Child health and lifestyle factual survey, FY2016 report,” by Adachi Ward Education Committee, Adachi Ward; the Center for Clinical Research and Development, National Center for Child Health and Development; Department of Global Health Promotion, Tokyo Medical and Dental University (April 2017)

While study and other forms of cognitive ability are important, so too are non-cognitive abilities required to become members of society, such as patience, motivation, cooperation, and communication.

But here, too, poor households are disadvantaged. A survey looking at households in Tokyo’s Adachi Ward reveals that children from poor households have a lower “ability to overcome adversity” than children from normal households.

Non-cognitive abilities also impact on whether a child has a positive attitude to study, and it is easy for children of poor households to fall into a vicious circle when it comes to skills formation.

If a child suffers from poor health, then it can be difficult to maintain continued employment as an adult, with an associated risk of lower lifetime earnings.

In poor households, children tend to have unbalanced diets and are more susceptible to obesity; this, too, leads to greater future health risks.

It is likely that parents who work long hours, or who work late at night or early in the morning, do not have the time or capacity to ensure their children are eating and living healthily on an everyday basis.

Percentage of obese children, by household type (FY2016)

- Note 1:“Households facing financial difficulties” are defined as households that fulfill at least one of the three following criteria: a household income of 3 million yen or less; a household with a lack of daily necessities; a household that has had difficulties meeting payments in the past

- Note 2:Numbers for “Obese” refer to the percentage of children classified as “Having a propensity for obesity”

- Source:Compiled by the Daiwa Institute of Research, based on “Second Child health and lifestyle factual survey, FY2016 report,” by Adachi Ward Education Committee, Adachi Ward; the Center for Clinical Research and Development, National Center for Child Health and Development; Department of Global Health Promotion, Tokyo Medical and Dental University (April 2017)

Through skills and health disadvantages, child poverty increases the likelihood of a future deterioration of human capital.

In Japan, innovation ought to be used to increase per person productivity; going forward, the quality of its human capital will become more important than ever before.

Since child poverty results in the continued deterioration of human capital, it will also lead directly to long-term falls in Japan’s capabilities as a nation.

Child poverty, which is frequently hidden from view, is thus a significant risk for Japan.

The following video, recorded in June 2018, provides a commentary on this report <Japanese only>

Related reports are also available to view online <Japanese only>